Your Paintings Don't Get Better Over Time

They also don't get worse. Careful how you manage your expectations!

A preamble - these writings will always be primarily ‘notes to self’- a way of stating perceived truths at this fairly late stage of the game. For us old timers who have been painting for decades certain things become noticeable. It’s a natural thing to want to, and expect to, get better and better at your craft as you age. In the first 10 years of painting, I think you do learn in leaps and bounds, conceptually and in terms of skills development. But at a certain point you level off and it’s harder to climb higher. Athletes notice this. Billiard players notice this. And I’m sure practitioners in many fields find this to be true.

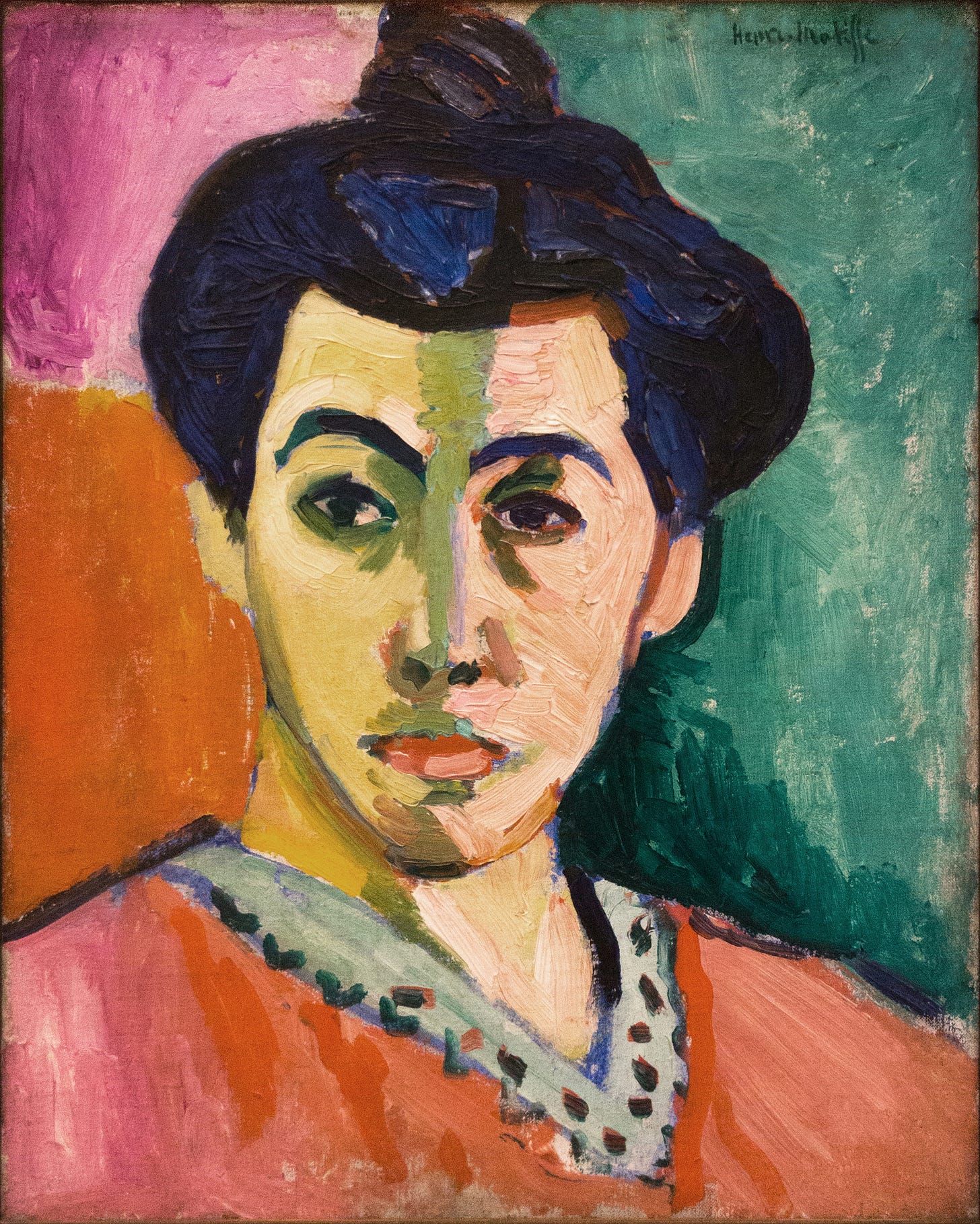

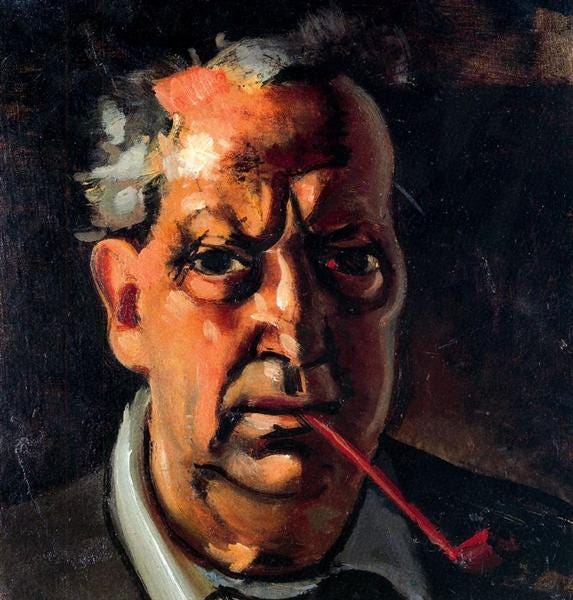

I often like looking through my image archives. The self portrait above was from the late 1980s or early 90s. Sometimes I’m very pleased by what I find in my files. Since my paintings and drawings were never about technical refinement or surface sophistication, and are not about moving towards some sort of commonly held idea of realism, I’m not surprised that the look of the work has not changed all that much over time.

It seems that I have always believed that there should be a bluntness of approach in the work. Technique should NOT be overly polished, because that would sidetrack from more essential issues. And the marks made in the piece should come as something of a surprise so that there is some hope of them creating a magic with everything else in the mix on the picture plane. This cannot be overly planned and has to be allowed to emerge through process.

And as I look through these early works (Bouquet, above is from the late 80s) I often see that this was the intention and the excitement that drove the work. And I often judge these works to be as good as, or even better, than what I can produce today.

In some ways that’s discouraging because you constantly want to exceed past abilities.

But one comfort here is that you have to make sure that you choose a large and worthy goal right from the start. And the goal even way back then was to create this sense of life that is beyond one’s grasp. It was not simply to put down what was understood. The statement had to be arrived at by trial and error. And the picture always had to be breathing, and also shocking in its stillness. A picture should not be easy to dismiss or simply pass by. It has to stop you…but exactly why it does that is not so easy to say.

Wheelbarrow, late 1980s.

So I’m happy to see these qualities in early pictures. And I’m happy to continue every day to find interesting surprises. The real test should be if you want to continue with the enterprise with full excitement, and without a reliance on extrinsic motivation (for example the desire for money or recognition). This is the only real way to continue, and this is the example that artists have shown us before. This was how Picasso and Matisse worked til their deaths.

On Buckhorn Lake, above, a Stooshinoff from the early 1990s.

Last Snow Patch, above, a very recent Stooshinoff piece.

At a certain point you have to let go of the ‘is it better or worse’ question, and just be satisfied if you’re fully motivated to go on. And ultimately we should leave it to someone else to evaluate the final merits of our contribution. Why drive yourself crazy when you have meaningful work to do?

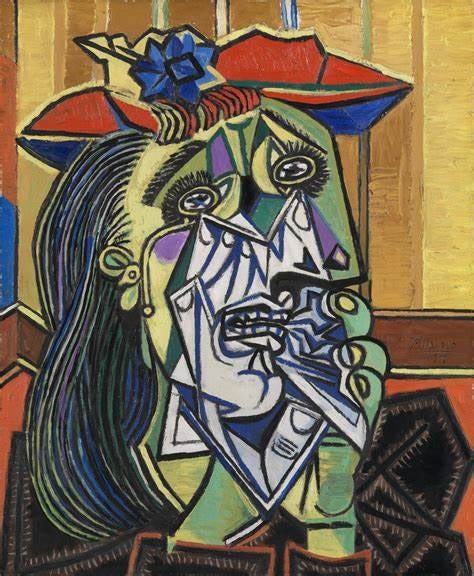

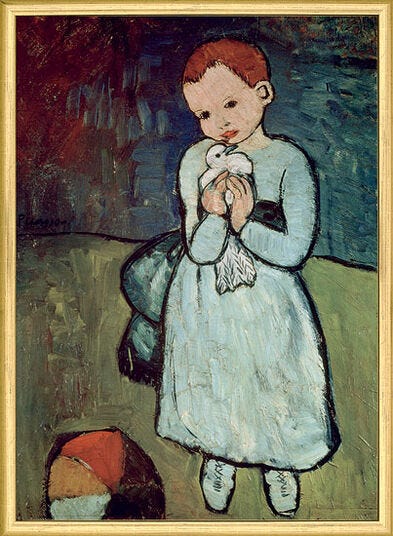

Picasso’s work was often so revolutionary that he wondered if what he was making was any good at all, but it sure didn’t stop him or slow him down. And is a Picasso work from the 1930s, Crying Woman better than Girl Holding a Dove from the Blue Period?

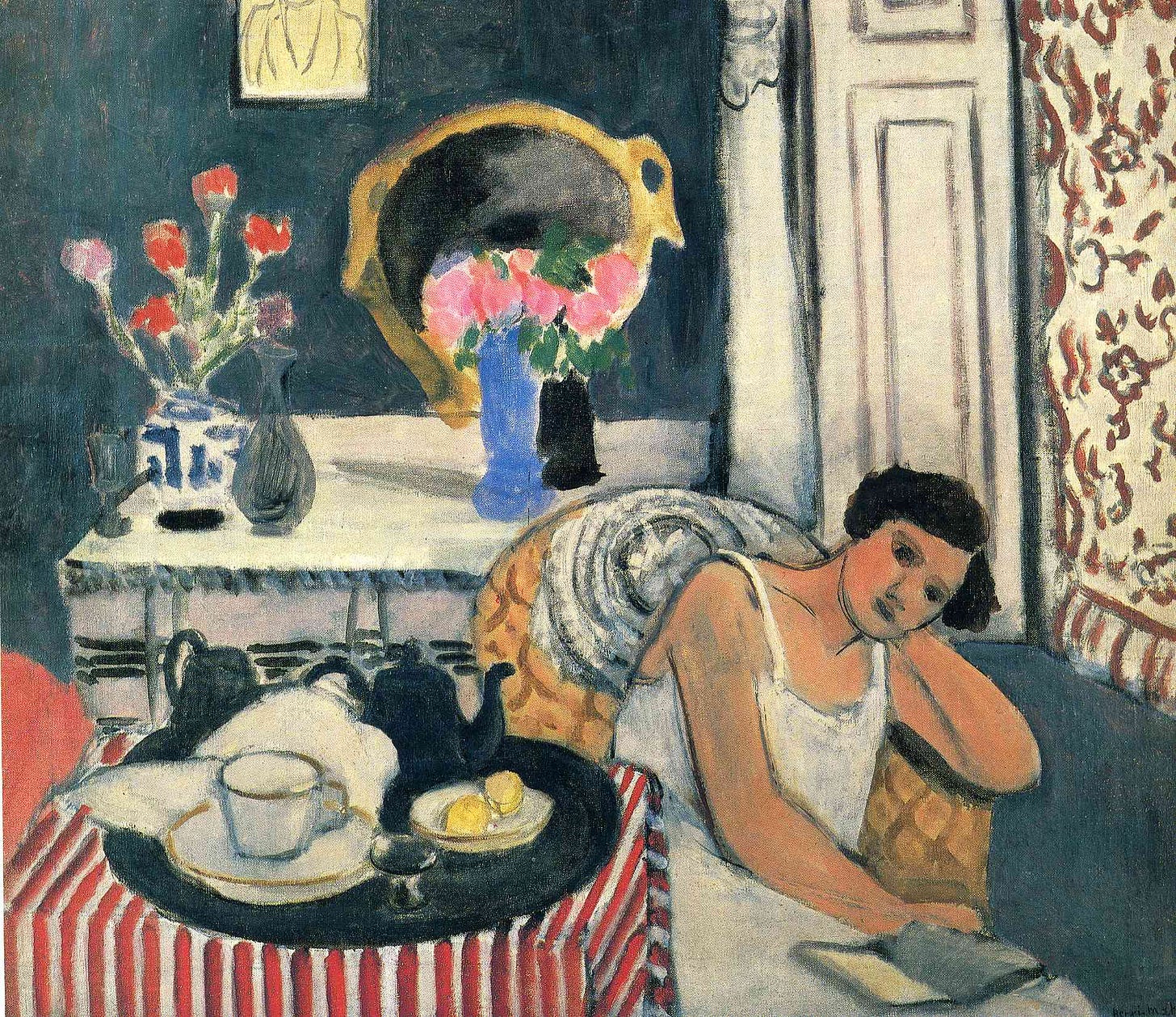

Or regarding Matisse….is the later Woman Reading better than the early Fauve piece, The Green Line? In many ways the question seems ridiculous because we only ask that the work affect us strongly and positively, and if that is accomplished, aren’t we being outrageous with our qualitative slicing and dicing?

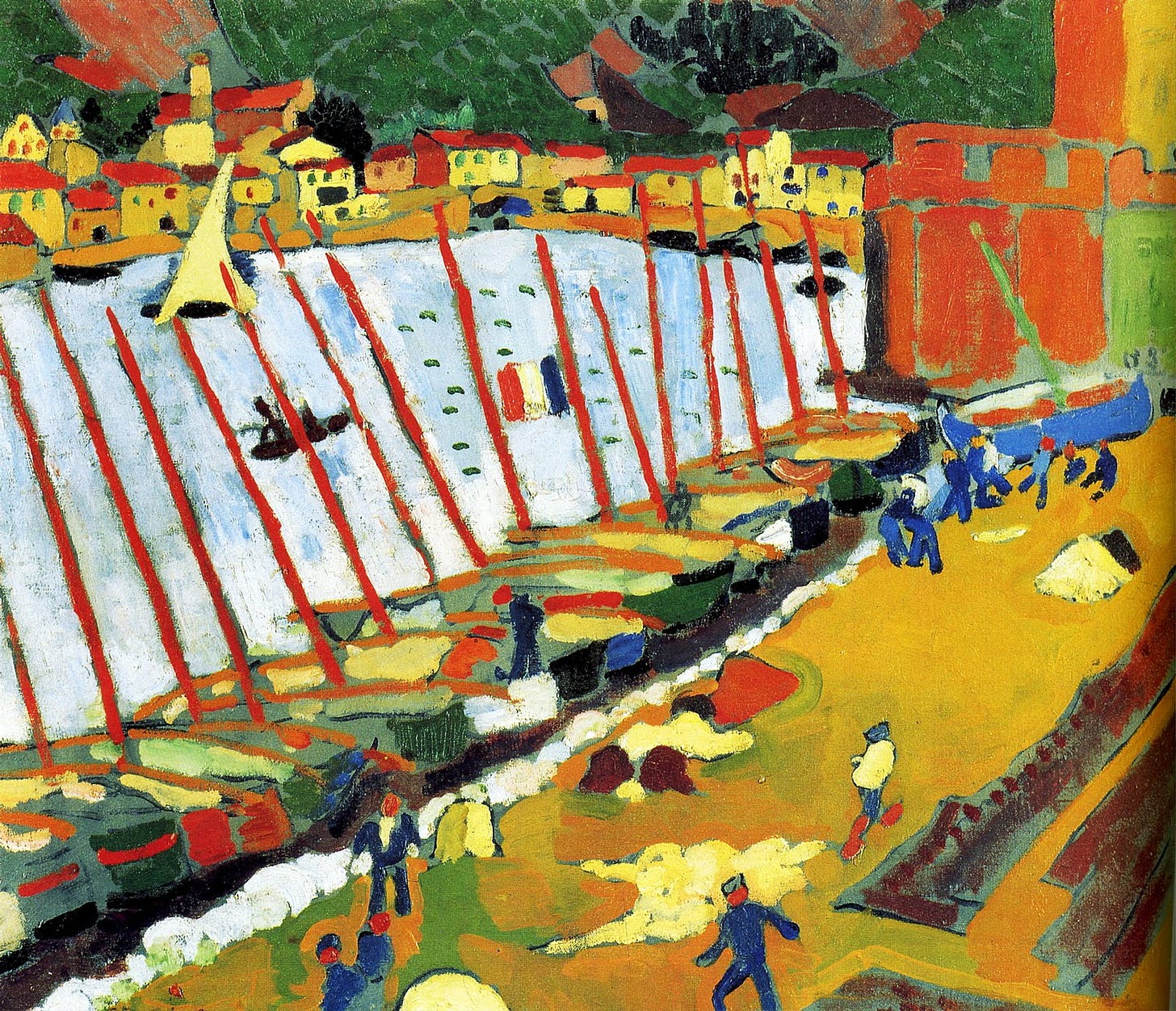

And then there is the example of Derain, whose early Fauve works were brilliant and equal in quality and influence to Matisse’s efforts. And yet critics often point out that later works lacked the daring and force of his Fauve period. Certainly Derain wouldn’t have agreed when he was in the midst of the later pieces. And…even if the later pieces ARE weaker (and I’m not saying they are), does it matter? From the standpoint of the artist…it really doesn’t. Your only yardstick should be….how much energy and full involvement can you bring to the task?

An early Derain Fauvist piece, and his later Self Portrait with Pipe, from 1953.

New Stooshinoff works are listed daily to:

Very timely post for me. I am in the process of creating an archive of images of older work and it's been interesting engaging with those images again and seeing "me" in them, albeit a much younger version!

Super helpful Harry. I can benefit from hearing about the energy your are trying to make visual in the paintings. Thank you for the inspiring words!